The William Benton Museum of Art Voltaren Reality Tour

Contact: Benton Museum Instruction Section at 860-486-1711.

A selection of the Museum's mola collection is available to tour local schools. Docent visits and talks at schools are as well available.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS and CREDITS:

This collection is a gift to The William Benton Museum of Art by Theodor Hans in the retentiveness of his married woman Elisabeth Hans.

The spider web presentation of this collection is made possible with a "Museums for the Millennium" grant, a Connecticut League of History Organizations initiative funded by SBC/SNET.

We would like to thank the post-obit people for their help with this project and the initial exhibition: Professor Paul Goodwin who wrote the historic data; Ann Parker and Avon Neal who provided expert information and intrepation of the Benton Museum's molas and Anna Hoover who volunteered her time for the legwork on this spider web project, and Karen Sommer who obtained the grant and coordinated the cosmos of this site.

Reference: Ann Parker & Avon Neal, Molas, Folk Fine art of the Cuna Indians, (New York, 1977)

The images are for educational purposes only and represent a sample of the collection. For permission to publish, please contact carla.galfano@uconn.edu (860-486-1717), The William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Farther READING ON THE KUNA AND MOLAS:

James Howe, The Kuna Gathering: Gimmicky Village Politics in Panama (Austin; 1986)

Clyde Due east. Keeler, Cuna Indian Art: The Culture and Craft of Panama's San Blas Islanders (New York: 1969)

Joanne M. Kelly, Cuna (New York: 1996)

Karin E. Tice, Kuna Crafts, Gender, and the Global Economy (Austin; 1995)

Jorge Ventocilla, et al., Plants and Animals in the Life of the Kuna (Austin: 1995)

The Molas of San Blas Islands: A Historical Perspective

Dwelling to Kina Indians, the San Blas Islands stretch forth the Atlantic coast of Panama from Colon to Colombia. In 1938 the islands and next coastline, the Comarca de San Blas, became an autonomous land inside Panama with a Panamanian governor on the island of Porvenir as liaison between Kuna village chiefs and the national government. Isolated for much of their history, the Kuna only grudgingly accommodated to some aspects of Western civilization. Contact with the Kuna has increased dramatically since the 1930's and during and after World State of war Two; today, cruise ships anchor off the islands on a regular footing.

Most of our knowledge of the early on history of the Kuna is drawn from the English language surgeon-cum-pirate, Lionel Wafer, whose shipmates left him in Panama in 1681 to recover from a gunpowder accident. He was cared for by isthmian natives knows as the Kuna, who preferred the English language to the Spaniards, the latter whom they took great honor in killing. Wafer advisedly chronicled the lives and community of the tribe and accurately described animate being and constitute life. He wrote of a matrilineal gild, where property was passed through the female person line. The woman'due south family unit chose her mate, who then moved into her household. Wafer was astounded by what he called "white Indians" living amidst the Kuna. Actually they were albinos; mayhap the globe'southward highest incidence of albinism is constitute on the San Blas Islands. Male person albinos were, and still are, treated as women.

Wafer was also intrigued by the custom of body painting: "They fabricated figures of birds, beasts, men, trees, or the similar, up and downwardly every role of the body, especially the face…. The women are the painters and take cracking delight in it." This is the likely origin of the colorful mola, literally "wearable", "dress", or "blouse". Today the term has come to hateful the appliqued panels of a Kuna woman's blouse, which have gained renown equally a distinct form of folk art. The transition from body painting to the mola, in the words of Ann Parker and Avon Neal, "could never have developed without the cotton fiber cloth, needles, thread, and pair of scissors acquired by trade from the ships that came to castling for coconuts during the 19th century", or, it might be added, from the insistence of missionaries that the Kuna wear clothing.

For Kuna women, the range of themes for torso painting was diverse; the range of themes for their molas appears endless. While designs of the earliest molas tended to be geometric abstractions, by the 1940's Kuna women had kindled an interest in the recreation of traditional themes common to body painting, e.g., the animals, trees, and men mentioned by Wafer, and had introduced new designs such as circus posters, comic volume characters, United States Navy blimps, and advertizement logos. The appearance of themes from "western civilization" does not automatically imply, even so, that the indigenous culture of the Kuna is somehow doomed. On the contrary, the Kuna have made meaning choices that simultaneously preserve the traditional and cater to the modern. Viewed from the perspective of the historian, the body painting of the 17thursday century and the fabric creations of today show how Kuna women, through their designs, capture unique images of the world in which they lived.

Karin Tice's splendid study of Kuna Crafts, Gender, and the Global Economy, notes that the "shift from sewing molas for personal employ to producing them for commutation on the global market place has affected mola sewers and their relationship to their arts and crafts profoundly". In the 1960's, molas became a article and those actually worn by Kuna women became especially prized. Growing world need for their creations convinced Kuna women to produce molas for the global market. As acknowledgment of their commercial importance, by the 1980's Kuna women who accept kurgin, defined as special gifts and talents in design, accomplish positions of loftier prestige in many communities.

In the 1990s, wholesale buyers tried to impose constraints on the producers, demanding color combinations more appealing to Europeans, different size and shapes, and themes that would cater more to "western" tastes. Because of the demand for acquirement, the Kuna take complied. For example, one buyer wanted snowmen. Although the women had no idea of what a snowman was, where he lived, or what he ate, they sewed snowmen. In Tice's words, "These molas produced specifically for sale were not worn by Kuna women' they were valued because they generated income".

Unfortunately, the popularity of molas has stimulated a large industry that churns out copies of Kuna designs on everything from fake molas, i.e. not sews by Kuna Indians, to shopping bas and coasters. Unauthorized reproduction threatens what the Kunas' greatest source of revenue. Despite Panamanian legislation passed in 1984 to protect its folk art, imitations of Kuna molas and pattern continue to flood the market.

But the marketing of molas should not obscure their real purpose as an expression of cultural identity. Tice observes that "wearing molas symbolically expresses Kuna indigenous identity and…a desire for autonomy from the not-Kuna globe". Some Kuna communities insist that women wear molas as an "important mode of upholding and valuing their traditions and therefore their identity equally Kuna people". Women run up molas to generate revenue, but they article of clothing them to express something specific, from social or political commentary to the delineation of an result. A favorite political candidate and the political party's logo and slogan might announced on one mola, and a child being eaten by an alligator might grace some other. Tice states that, in the latter example, the Kuna mother wanted to impress on her children the dangers posed past certain animals. Despite their product for the globe market, moals are yet sewn for personal use and serve an important role inside Kuna society as "a medium for social commentary, for personal inventiveness, and for fashion".

Although molas as a commodity plant stiff markets in Europe, the Us, and Nihon, until recently Panamanians did not buy them in big part because they viewed folk fine art as "inferior". All the same, the buy of molas past Panamanians became significant afterwards the invasion of Panama past the U.s. in 1989. While many in Panama detested Manuel Noriega and his henchmen, nigh resented the United States' solution to the trouble. Ownership and wearing molas, which represented something that was indisputably Panamanian, became a quiet form of national protest against the forceful strange policy of their northern neighbor. And, in the 1990s, what had been an expression of national pride became acceptable every bit style. Responding to the high praise for molas exterior Panama, the upper classes of the country take also accepted them as fashion.

Molas, and so, have historically served a diversity of purposes. They have expressed Kuna traditions and independence and have protected Kuna culture; they have commented on Kuna society and expressed opinions nigh Panamanian politics and politicians; and they accept expressed the national pride of all of Panama in the confront of an interventionist United States. Although many are still intensely personal, nigh are at present rather impersonal items for sale abroad; for the outside world every bit well every bit for Kuna women, they accept become fashionable. Only to capeesh fully and understand them, we must see them first and foremost in the traditional context of the community.

Profeessor Paul B. Goodwin

Acquaintance Dean, School of Arts and Sciences

Academy of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Molas are simple yoke-type blouses richly decorated past intricate needlework. Mola can hateful the blouse that is daily clothing for Kuna (sometimes spelled Cuna) women only most often refers to its front or dorsum panel. They have been made for about a century. The long shifts that were get-go worn were cumbersome and soon crept upwardly to blouse length, to be paired with a unproblematic sarong. Early on loose-fitting molas gave way to blouses of smaller size. What inspired Kuna woman to have upwardly the very difficult reverse appliqué technique is unclear. Each panel is constructed of multiple layers of textile of contrasting colors. The layers are carefully snipped, peeled back to reveal the underlying colors and stitched together to create the pattern. The technique is sometimes referred to as opposite applique. Molas can often have every bit many every bit four colored layers of cloth with extra colour pieces and embroidery accents added. It takes many hours of sewing to create even the simplest mola.

The first designs that Kuna women adult for mola panels relate to the body painting that had been traditional for centuries. Mola-makers transformed images of daily life and of the flora and fauna of their islands into mola designs. As the outside world impinged on the Kunas more and more than, book and magazine illustrations, record covers, and other images and objects that the men of the islands brought back from nearby Panama Urban center as well attracted Kuna women.

The molas in this collection date from the 1940s to the 1980s. Many of them, particularly the earlier, are almost never to exist plant whatever longer. Now that the exterior world has discovered molas, Kuna women sell many of them and thereby find status and power across that provided by their traditional matrilineal society. The rest of Panama has discovered molas too, and they are worn today as a symbol of national identity. Kuna women go along to sew molas for themselves and keep to vie with i some other, as they long accept, to create the nigh dazzling designs. Girls sew as presently as they can handle a needle and, like their mothers, spend hours every day of their lives designing and making molas.

A discussion about the cotton that is used in molas — the cotton fiber is thousand cotton fiber from the commercial world. It is said that the cotton wool fabric comes from Bharat or more unremarkably Frg. The fabric is unremarkably colorfast and is the kind of fabric that one would notice in stores in the United States or in other countries. At that place is cypher indigenous virtually information technology. It is brought on the trading boats from Columbia and is one of the main items traded to the Kunas for coconuts.

When looking at the molas in this web exhibition, information technology is important to remember that they were all part of blouses that are part of the everyday wear of the Kuna women. Regardless of their design – political, genre, flora and fauna, abstract, illustrational, etc. – their primary interest to the Kuna is visual and decorative.

Thomas Bruhn, Curator of Collections (retired),

The William Benton Museum of Art,

Academy of Connecticut, Storrs.

A Souvenir of Theodor Hans in Memory of his Wife Elisabeth Hans

In 1963 Elisabeth Hans made her first circuit to the San Blas Islands forth Panama's Atlantic declension, home to the Kuna Indians. Her married man Theodor Hans, a United states Civil Service employee, had been assigned to the U.S. Army Southern Command in the Panama Culvert Zone in 1962. He recalls that the tropical climate and lush vegetation strongly impressed her, and while visiting the nearby islands she was immediately drawn to the colorful and unique mola blouses worn by the Kuna women. She acquired her first two molas and and then began a collection that would continue to grow over the course of thirty years.

As she connected to collect in the 1960s – and even came to empathise the Kuna language to some degree – members of the U.South. Armed services, diplomats stationed in Panama, and important visitors to the expanse contacted Elisabeth Hans to obtain the best molas. Her activities as a collector and advisor led her to open a specialty shop, Arte Caribe, in Panama City in 1970. Here she sold molas also as other objects crafted by native artists and artisans from all over Latin America and the Caribbean. She remained with the shop until 1977 when she and Theodor Hans moved to Munich, Deutschland. Of the estimated 30,000 molas she had collected, she brought 16,000 to Federal republic of germany. From 1977 until her expiry in 1993, she owned and operated an consign-import firm for Latin American native crafts. Many mola collectors and friends not but respected her equally an expert on molas only for her dandy kindness, generosity, and skillful humor.

With Theodor Hans' souvenir, the Benton Museum has become home to 300 pieces from Elisabeth Hans' extraordinarily rich collection. Thank you to his generosity and the passionate collecting of Elisabeth Hans, visitors to the Benton Museum tin ever enjoy this intricate art form.

This collection is a gift to the William Benton Museum of Fine art by Theodore Hans in the retentiveness of his married woman Elisabeth Hans

The web presentation of this collection is made possible by a "Museum for the Millenium" grant, a Connecticut League of History Organizations initiative funded by SBC/SNET. The images are for educational purposes only and represent a sample of the drove. for permission to publish pleas contact The William Benton Museum of Art , University of Connecticut, Storrs, 860-486-1707.

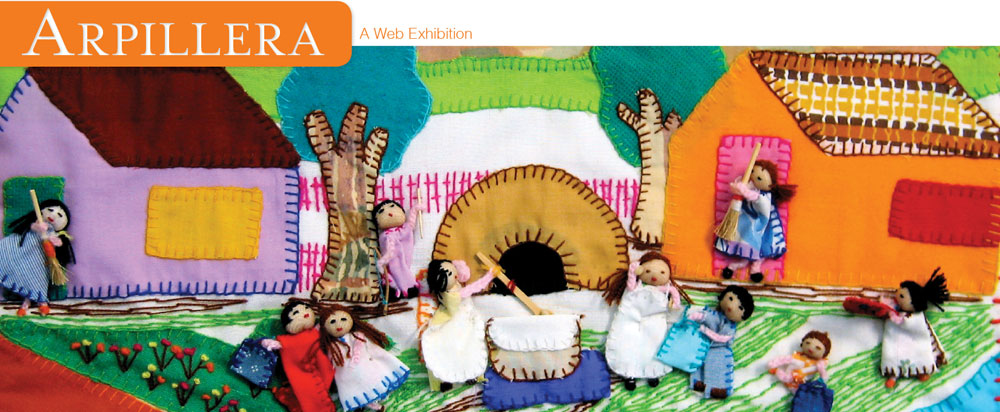

3 Dimentional Appliqué Textiles of Chile, c. 1985 – 1998 Sewing for Resistance

From the Instruction Drove of The William Benton Museum of Art

The images are for educational purposes just and present a sample of the collection. For permission to

reproduce, please contact the Registrar at The William Benton Museum of Art, Academy of Connecticut, Storrs, 860-486-1707.

Like many people in the rest of the globe, the rock singer "Sting" was moved by the courage and pain of the women who were relatives of the "disappeared and detained". He visited Chile and the arpillera workshops and was especially touched when he witnessed these women doing the GUECA, a traditional Chilean courting trip the light fantastic that is performed annually. The women were dancing lonely, wearing a photo of their husband or lover who was gone on their blouses.

Album notes from They Trip the light fantastic Alone. "On the Amnesty Bout of 1986 the musicians were introduced to former political prisoners, victims of torture and imprisonment without trial from all over the world. These meetings had a strong impact on all of u.s.a.. Information technology's ane thing to read about torture, but to speak to a victim brings y'all a pace closer to the reality that is then frighteningly pervasive. We were all deeply affected."

Written and recorded By "Sting"

From the albumNothing Similar the Sun

Why are these women hither dancing on their ain?

Why is there this sadness in their eyes?

Why are the soldiers hither

their faces waxed like rock?

I can't encounter what it is that they despise

They're dancing with the missing

They're dancing with the dead

They dance with the invisible ones

Their anguish is unsaid

They're dancing with their fathers

They're dancing with their sons

They're dancing with their husbands

They dance solitary They dance alone

Information technology's the but but course of protest they're allowed

I've seen their silent faces scream so loud

If they were to speak these words

they'd go missing also

Another woman on the torture table

What else tin can they exercise

They're dancing with the missing

They're dancing with the dead

They trip the light fantastic toe with the invisible ones

Their anguish is unsaid

They're dancing with their fathers

They're dancing with their sons

They're dancing with their husbands

They dance lonely They dance alone

Ane day we'll dance on their graves

One day we'll sing our freedom

One twenty-four hours nosotros'll express joy in our joy

And we'll dance

One mean solar day nosotros'll trip the light fantastic toe on their graves

One 24-hour interval we'll sing our freedom

One mean solar day we'll express mirth in our joy

And we'll trip the light fantastic toe

Ellas danzan con los desaparecidos

Ellas danzan con los muertos

Ellas danzan con (the invisible ones)

Their ache is unsaid

Danzan con sus padres

Danzan con sus hijos

Danzan con sus esposos

Danzan solas

Scraps Of Life: Chilean Arpilleras, by Majorie Agos'n (Red Sea Printing, 1987)

Chilean Women and the Tapestries of Solidarity,a paper article past Marcelo Chalin, a Chilean architect doing graduate work in sociology at York Academy in Toronto, Canada. The article appeared in the campus newspaper of York's Atkinson College in September 1983.

Farther READING ON THE ARPILLERAS OF Republic of chile:

Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love: The Arpillera Move in Chile by Marjorie Agos'n

Why Women Protest: Women's Movements in Chile (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) past Lisa Baldez

A Language of Women A pick of pieces of literature by Chilean women writers.

From "Chilean Women and the Tapestries of Solidarity"

They speak with a language that comes shut to the extremes of life and death. Here we have a language of women who often have difficulties in speaking or writing "properly," or in speaking before groups. Here we have women who take created a new language, one that tin be understood by everyone and which creates bridges. Over these bridges, in i management, comes support from those who have not been directly affected past the situation in Republic of chile, and also from those who have. In the other direction comes, from the once defeated,their version andtheir vision, their side of the story is an irrefutable mode. How, otherwise, tin can a woman from a poor neighborhood at the other stop of the world, someone who has seen the abduction of her hubby or the death of her son, leave an indelible testimony of her hurting? How else can she tell us virtually her life from then on?

Thousands of anonymous women take done it with their tapestries.

As in all languages, this ane too has evolved, as accept the arpillera makers. If in the beginning they were persons searching in despair, through their own work they now amend understand their condition, the reasons for it. It is no longer a question of fate; their understanding has become political, as have their organizations and their actions. They do not inquire any more, they demand; they no longer hibernate, they strike, they protest, and they express it through their tapestries. These are the same women who become on hunger strikes, who concatenation themselves to doors of the Supreme Court enervating justice, who pilgrimage to the execution sites, who march in the streets with loud voices. Then they get back to their workshops and tell us of their chaining, their hunger, their anger, their victories. They write nevertheless another folio of their testimony.

These handicrafts correspond no less. The arpilleras take succeeded in telling and transforming, 2 basic qualities of whatsoever language. They are giving united states of america a vision of reality which otherwise would have been lost, and at the aforementioned time they are transforming that same reality they are portraying. From this indicate of view, the arpilleras represent not-vehement, revolutionary language. They marking the nature of the Chilean resistance. These women accept not been using the pocketknife, they have non needed or wanted to kill. They have created their ain effective words to draw the actions of others and their own.

"Chilean Women and the Tapestries of Solidarity," a newspaper commodity past Marcelo Chalin, a Chilean architect doing graduate work in sociology at York University in Toronto, Canada. The article appeared in the campus newspaper of York's Atkinson Higher in September 1983.

From "Scraps of Life: Chilean Arpilleras". Pages 51-52.

Technical assistance for making arpilleras was provided past volunteers trained in the plastic arts, women like Valentina Bonne, a painter. According to the accounts of the women, they were told first to make scenes of their daily life, the things they saw and to limited what they felt. They began by cutting out little figures, but they were apartment lifeless and without movement. Their starting time houses were all like and made of gray material. The women themselves say they never thought anyone was going to purchase what they were making; that they were ugly and that nobody would exist interested in the lives of poor people.

Later on this stage, however, the women learned to observe more carefully, and it was as though in trying to run into their own modest surroundings with more than clarity, they were led to a clearer vision of what was happening in the country. "I walked around like and idiot," one woman told me."I looked closely at everything. I believe I learned how to run across."

An artist writes of the offset of arpillera making:

After the military insurrection I was out of a job like so many others. In a brusk time the Pro-Paz committee asked me to develop some craft piece of work projects with women. The first group assigned to me were women of families of the detained-disappeared: mothers, wives, sisters. At the end of my interview with them, it was clear to me that in their land of anxiety they would not be able to concentrate on annihilation simply their own hurting. I could hardly believe what I had heard, sons, husbands, brothers, snatched with bows and threats to their families, pregnant women carried off, couples including their pocket-size children, all disappeared for weeks and even months, with nobody knowing anything about them, not seen nearly newborns or the older children and even less about the adults.

Everything I had been thinking about doing with these women was useless, since the hereafter work we would undertake together ought to serve equally a catharsis. Every woman began to translate her story into images and the images into embroidery, but the embroidery was very slow and their nerves weren't up to that. Without knowing how to keep I walked, looked, and thought, and finally my attention was attracted by a Panamanianmola, a type of ethnic tapestry. I remembered also a foreign fashion very much in vogue at that time: "patchwork." Very happy with my solution the very side by side day we began collecting pieces of textile, new and used, thread and yarn, and with all the material together we very quickly assembled our themes and the tapestries. The histories remained like a true testimony in 1 or various pieces of textile. It was dramatic to come across how the women wept as they sewed their stories, but it was besides very enriching to encounter how in some way the work also afforded happiness, provided relief.

The words of 3 arpilleristas: Two stories and a poem

Santiago, Jan 14, 1985

My story is very simple and more than than that sorry. I vest to the Clan of the Families of Detained-Disappeared and am arpillerista at the same time. When I make the arpilleras I am thinking not only of my own problem, but of all the families without stardom because of political beliefs. This piece of work is done under the fly of the Vicarate, that also buys the piece of work from us, that helps us survive. The piece of work began ten years agone, with the disappearance of thousands of Chileans beginning from the 11th of September, 1973. The suffering and anguish for my girl, daughter-in-law, and petty grandchildren and myself is very great, but notwithstanding I don't lose promise of seeing my son alive again. By A mother.

A verse form:

I WOULD LIKE You TO KNOW MY SON

THAT YOUR Name RUNS

THROUGH THE BEADS OF MY ROSARY

To recall that they made you disappear

Simply after you reached your 22nd year

If you know son

How I search for yous from dawn to dusk,

I know that your ideal was just

For your people, now their rights

Are trampled on.

No longer are you with your people

But I will take your place

Because I am sure one day

Our people will be freed.

I wanted to kill myself if my son didn't come back within vi months. But subsequently my companions told me to resign myself, that we all had the aforementioned pain, that they were suffering the same.

So my fight began, I said to myself I had to survive this blow because I have to know where my son is and I have to see that man fall who is in the government.

The other women of the Association of the Detained-Disappeared welcomed me very warmly and I began to gain strength and courage and began to take legal steps possible after the detention of my son.

A lawyer fabricated the appeal for the protection of civil rights that I personally carried to the Supreme Court. I began to brand the rounds of all the hospitals, the morgue, the Psychiatric Hospital, the International Ruby-red Cross, the different detention centers, I covered all the jails of the zone.

At this time the Association of the Detained-Disappeared had a van for the use of us family unit members who were searching for a detained one. Through the Vicarate of Solidarity we could talk with other political prisoners and ask them if they had seen my son, we took photos for them to come across when nosotros made our inquiries.

That's how I knew my son was detained in Villa Grimaldi. Six people swore before a minister of the court that they had seen him at that place, that he was all right, that he hadn't been tortured, but one night they had him say expert-adieu to his friends because he was being released, and since then naught more has been known of him up to this date.

From "Scraps of Life: Chilean Arpilleras" by poet and human rights activist, Marjorie Agos'n, a professor of Latin American Literature at Wellesley College.(Blood-red Sea Press, 1987).

Source: https://benton.uconn.edu/tag/online-exhibition/